The first “real” photo I took, the photo that made me breathless for a moment, was this one I call, Heron Flying in Snow.

It was winter. Snowing. My favorite time to walk the river after the fall anglers and cane pole fishermen have left to linger over small tables with bobbin holders and hair stackers, tying their lures and flies of deer hair and feathers before the bright fires I wish for them.

For me, the wish is winter solitude. Their leaving gives me that: frozen lakes and river banks where I can walk in quiet with my camera in hand, winter steam rising over the resident birds I have grown to love.

For most of my life, I have tried to catch and hold light only in words. Beautiful words, I always hoped. But I remembered WH Auden’s poem, “Musee des Beaux Arts,” musing over Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. I think this poem and this painting were my first time experiencing the “ekphrastic” and the power of image and word wedded together. Amidst furrowed fields and herds of sheep and the soft blow of ship sails against pale green harbor water, two tiny half-white dabs of paint in the right-hand foreground of this landscape are all that depicts the fall of poor Icarus, a boy dressed by his father in wings of wax and honey, the boy who almost touched the sun.

“About suffering, they were never wrong,” Auden teaches us in his poem, and today, for me, still, the “delicate ship” goes “calmly on,” while Icarus drowns.

My daughter and son-in-law gave me a camera for Christmas a few years back. That spring, during the pandemic, I took a Zoom naturalist course that sent me to the river and its byways, alone. “Record what you see with a camera or pen,” the Zoom naturalist told my class. And so began my journey into the ekphrastic and the ways of rivers.

“Ekphrastic!” I must first admit my husband sputters each time I use the word. “Exactly who knows what that word means?” he asks. “And it’s an ugly word, too!” he puffs at me as he fusses at his beloved fish tank.

But unlike my husband, I hear in that word’s first two syllables the echo of “ecstatic,” born from the Greek word, “ekstasis,” meaning “to stand outside” oneself, to “transcend.” And that is what I feel each time I mix the imagery of photo and word together.

The heron, I remember, startled me as much as I startled it: the heron hunched at the shoreline, hidden by cattails, suddenly popped its wings open at my winter stepping and floated toward the river, its shock of feet dangling in the snow dusk like a pen’s mark, the heron now something caught and lit within me.

After seeing a photo I took in a canyon of a grass skipper with the butterfly’s surprise of tiny orange knobs on its antennas, someone said to me on Facebook, “I see a book.”

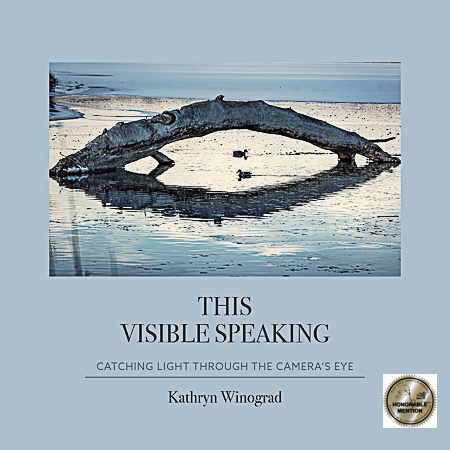

Since those words, there have been all kinds of light I have found in this journey. All this light in the visible speaking.